It is almost a mantra among piano teachers that they should teach artistry from the very first lesson. This sounds very lofty. It just sounds correct. How could anyone disagree with something so sensible?

As a young teacher I was convinced that this would be my approach. I was convicted to become the very best teacher I could be and that my students were going to become artistic performers. I always was patient but I kept my standards very high. I did my best to make sure there were no breaks in legato phrasing. Every dynamic change needed to be clearly discerned. We would work for perfectly timed ritardandos at the end of their compositions. Staccatos passages needed to be perfectly even in their duration. I would not allow a student to graduate from a piece until it was thoroughly mastered. When my students were judged in their Guild Auditions the judges were very pleased with my attention to detail. One judge told me that I brought each student to the potential of their ability. I was pleased.

I was teaching artistry from the very first lesson and getting good results. One year at Guild Auditions our judge was from the piano faculty of Carnegie Mellon University. Her name was Helen Gossard. She was quiet, well spoken and very intelligent. I had the opportunity to speak with her several times during her stay judging my center, since I was the chairman of the center. I give her credit for helping me look at artistry from a different perspective.

I remember her telling me that she would give a student credit for simply making a good effort at playing a staccato passage. I thought differently. A good effort isn’t enough. It must be done properly. I mentioned previous judges comments that they appreciated my attention to detail. She mentioned the work of another teacher in my center, a teacher in her 60’s when I was in my 30’s, who had much more experience than I. She mentioned the high quality of her work. I had to admit to the high quality of her work, though I thought I did a better job in teaching musical detail. Ms. Gossard told me that the detail she taught was very good.

This experience got me to start thinking about my teaching and to consider if I was missing things because of being so strictly focused on performance artistry. I questioned this not because I didn’t have a full class of students or that students were quitting, in fact, I would even inherit a few of this other teacher’s students through transfers.

I began to consider that there were other ways to consider artistry. One important way is to consider the artistry of teaching itself, not only the artistry in performing music. Everything I was teaching was driven by artistry whether it was scales, arpeggios, chords, transposing, ear training, ….. everything. But giving thought to the artistry of teaching was a brand new avenue for thought that I had given very little attention.

I think one can learn a lot from observing artists in non musical fields and how they approach their art. One TV show I loved watching as a young child was a show where I could observe John Gnagy, an artist, drawing landscapes and other drawings.

Observing an artist drawing a portrait of a person is very much like a piano teacher forming (drawing) a young musician.

I think this analogy will help give you a different vision of how to develop a young musician. Yes, it’s full of detail, but it’s not a detail where one notices a perfection on individual parts but a detail of general shapes and patterns that eventually emerge into a beautiful picture. The artist will develop the portrait moving from place to place in the drawing adding more and more detail and the drawing emerges from the canvas. This is NOT at all analogous to the image of my teaching, where every element of their composition had to be perfectly mastered before I was satisfied to move the student to new repertoire.

SNIP 1 – THE BEGINNING

Here is the drawing at the very beginning of the process. There is no detail at this juncture, just a framework to get started. We cannot discern,with any certainty, the image from these elemental markings. I remember in my initial interview with a student as a young teacher I would ask the student very non musical questions. Can you say the alphabet to G? Can you say the alphabet backwards from G to A? I would play little games with the student to determine if they were right handed or left handed. I would ask the parent questions about their piano (no one had keyboards in the 60’s). I would ask the parent where the piano was in their home. I was just laying a framework of questions to see if we had the elemental markings necessary for a successful piano student. At least I was doing this right.

Here is the drawing at the very beginning of the process. There is no detail at this juncture, just a framework to get started. We cannot discern,with any certainty, the image from these elemental markings. I remember in my initial interview with a student as a young teacher I would ask the student very non musical questions. Can you say the alphabet to G? Can you say the alphabet backwards from G to A? I would play little games with the student to determine if they were right handed or left handed. I would ask the parent questions about their piano (no one had keyboards in the 60’s). I would ask the parent where the piano was in their home. I was just laying a framework of questions to see if we had the elemental markings necessary for a successful piano student. At least I was doing this right.

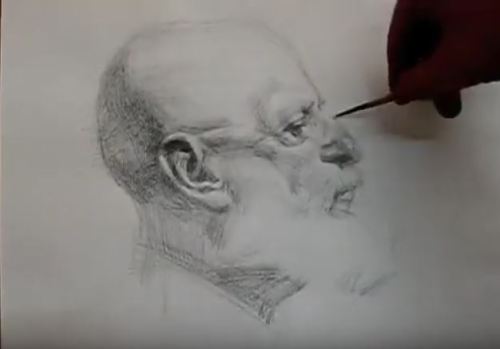

SNIP 2 – THE FIRST IMAGE

On the second image we can discern the outlines of a man. We have the shape of a head containing an ear, an eye, a nose, the beginnings of a neck and a mouth. We have a shape but we do not have detail. I can now see the concept of giving a student credit for attempting staccato even though it may not be executed with great precision and detail. In the first months of study it’s perfectly OK to be concerned with teaching the general “shape of staccato” but, this may not be the time to be concerned with great precision in the detail in its execution. That detail can wait for another time.

On the second image we can discern the outlines of a man. We have the shape of a head containing an ear, an eye, a nose, the beginnings of a neck and a mouth. We have a shape but we do not have detail. I can now see the concept of giving a student credit for attempting staccato even though it may not be executed with great precision and detail. In the first months of study it’s perfectly OK to be concerned with teaching the general “shape of staccato” but, this may not be the time to be concerned with great precision in the detail in its execution. That detail can wait for another time.

But, the obvious question is “What do we then teach?” “What do we do with the lesson time?” At this stage, you teach general musical shapes not being concerned with the detail that can wait for a future time. You learn to teach these basic concepts and be satisfied by the efforts of the student that they can achieve at that moment in their development. If eighth notes are not perfectly even that’s OK. As they develop, under you watchful eye, this will develop. There are certainly going to be many repertoire pieces that are going to feature eighth notes. But, to become fixated on the artistry of performance waiting for perfection from the student is like our artist working on the nose of his painting until it’s perfect in every detail before moving to the eye. We must learn to be much more holistic in moving the complete performance ability of the student in all its individual parts (shapes) forward.

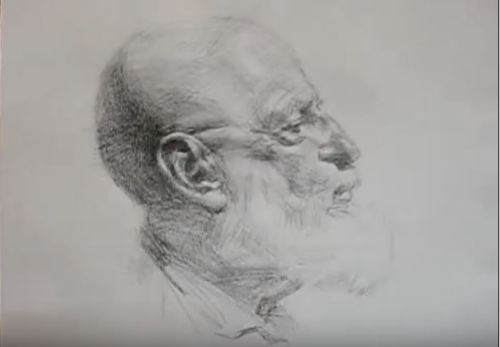

SNIP 3 – BEGIN DETAIL, BUT ONLY AT A MODERATE LEVEL

At the next level we begin adding some detail, but only at a moderate level. After the basic shapes are gently sketched out we are ready to begin filling out the detail. Also, the painting begins adding some issues of depth perception. Also, notice at this juncture, the back of the head and the ear is still only sketched.

At the next level we begin adding some detail, but only at a moderate level. After the basic shapes are gently sketched out we are ready to begin filling out the detail. Also, the painting begins adding some issues of depth perception. Also, notice at this juncture, the back of the head and the ear is still only sketched.

Applying this analogously to music performance we can make our students aware of some moderate level of detail in dynamics. We could make students aware of some basic details on music forms. Teaching, for example, about binary form is fine. But, going into the detail of key changes and modulation through the A and B sections is an example of adding more detail than is necessary at this stage. Some introductory comments about music’s style periods may be fine but the necessity of going into more detail isn’t necessary at this point. Again, think holistically. The goal is to keep in mind the whole image. We can make students aware of phrases in a general way but at this stage there’s no need to become specific or elaborate. The goal is to move all the individual parts slowly forward at generally the same pace. Why teach sotto voce when basic dynamic contrasts are not easily executable? Maybe our student, at this level, is having difficulty in keeping his accompaniments sufficiently soft. It would be a much better use of time to begin to work on this detail at a moderate level than the subtlety of sotto voce.

SNIP 4 – BE PATIENT! EVEN AT MODERATE DETAIL THERE’S A LOT OF WORK TO DO

At the intermediate level of this drawing there is a tremendous amount of work that needs to patiently be completed. One thing I discovered when I was on artistry from the very first lesson approach was that my students could play well. They scored very well at auditions and festivals, but they couldn’t read well. This was a direct result of not building the whole student and being overly focused on performance detail. It was actually a disservice to my students.

At the intermediate level of this drawing there is a tremendous amount of work that needs to patiently be completed. One thing I discovered when I was on artistry from the very first lesson approach was that my students could play well. They scored very well at auditions and festivals, but they couldn’t read well. This was a direct result of not building the whole student and being overly focused on performance detail. It was actually a disservice to my students.

Many young students get to the intermediate level in late grade school and middle school years. At this age their identity with popular music becomes very strong. It’s the music of their peers. Using popular music as a means to develop sight reading skills makes great sense. Give them popular music, a lot of it. It doesn’t even have to be at their performance level. Giving students music below their performance level is perfect for sight reading material.

I find popular music provides very good material for teaching students about phrasing and the singing musical line. It also provides good rhythmic challenges; different rhythmic challenges than classical music, but it is still good material for teaching students moderate level detail work for most students in their teen years.

But, there are many things that can be included in this intermediate level to be taught at a moderate level of detail. The four major stylistic eras can be explored with some introductory music history. An introduction to Baroque dances, an outline of the history of the piano, the association with composers to their style period would each make for a framework of study of music history to be fleshed out if lessons continue at a high school or collegiate level.

While students are learning their popular music, continue to work on developing the whole musician and work on music from every performance angle but still at a moderate level. We’re not teaching students at a graduate school level.

SNIP 5 – MORE PATIENCE! Ending Moderate Detail/Filling in the Gaps

Take time to think what are the basic shapes that need thought at the elementary level. Think of every possible musical shape. Often, we will think of rather sophisticated things, like unusual meters as 5/4 or 7/8. Ask yourself, “How can I best prepare my students for these meters in the elementary level as “basic shapes?” “How can I move my student from the elementary level to the intermediate level in teaching these meters?” What would these meters look like at a moderate level of detail? The goal is to lay the proper framework at the elementary level to move the student to the level of moderate detail and difficulty. To do this without proper preparation is going to take considerably more time than with proper preparation. Every part of our drawing begins with basic shapes before detail is added and piano teachers need to be thinking in the same manner.

Take time to think what are the basic shapes that need thought at the elementary level. Think of every possible musical shape. Often, we will think of rather sophisticated things, like unusual meters as 5/4 or 7/8. Ask yourself, “How can I best prepare my students for these meters in the elementary level as “basic shapes?” “How can I move my student from the elementary level to the intermediate level in teaching these meters?” What would these meters look like at a moderate level of detail? The goal is to lay the proper framework at the elementary level to move the student to the level of moderate detail and difficulty. To do this without proper preparation is going to take considerably more time than with proper preparation. Every part of our drawing begins with basic shapes before detail is added and piano teachers need to be thinking in the same manner.

The artistry of teaching is a very rich and rewarding enterprise but it only is achieved with a lot of active purpose and mental effort. It is also a very different enterprise that the artistry of performance even though it may use much of the same information.

STEP 6 – LET’S BECOME TRULY DETAILED

At this stage the drawing is really beginning to look like a work of art. An image is beginning to emerge.

At this stage the drawing is really beginning to look like a work of art. An image is beginning to emerge.

I look at this extended process as NOT going from Point A to Point B but rather going from Point A to Point Z. Going from Point A to Point B just requires simple easily discernible logic. Going from no dynamics to learning forte vs piano is a rather easy step from the point of teaching; though it takes some patience and insistence on the teacher’s part for the student to master this basic rudimentary means of expression. The same could be said for developing a staccato and a legato touch.

But, from going to Point A to Point Z is like the long process of learning to express the musical line. This is something that is well beyond the simple logic from going from Point A to Point B. Phrasing beautifully is a long journey that requires a sophisticated touch. It requires nuance. It required the development of an artistic sense to intuit the rise and fall of the melodic line. It requires a sense of a beginning leading to an end. It includes a sense of breathing. It includes an apprehension of the continuity of one phrase to the next. It requires “sound poetry”. I think if you would write your own list you could add many other very valid points. All this leads to the fact that for something as sophisticated as artistically expressive music lines, we have so many elements that it cannot possibly be taught as a Point A going to Point B. To burden an elementary student with this like asking a first grader to understand geometry.

It may be a good idea for a teacher to develop a repertoire of compositions that include your major points of phrasing you feel are musical necessities to great phrasing; in fact maybe have several pieces for each point. It may also be a good idea to make a list of several Point A to Point Z issues that need a long look for mastery. Understand meter, simple and compound through all the basic time signatures may be one. Understand piano technique would be another; moving the student from simple ideas to moderately sophisticated ideas to advanced ideas. It may be easier to just allow this to happen as the repertoire advances but isolating these issues would be advantageous to both teacher and student and really add the concept of the artistry of teaching.

STEP 7 – LET’S GET REAL!

Here’s the final picture in all its detail. What began as simple framework shapes is now a real piece of art. Developing a student as a “work of art” in itself requires thought of someone that approaches teaching itself as an art form and then superimposes his educational art upon his artistic craft of musical performance.

Here’s the final picture in all its detail. What began as simple framework shapes is now a real piece of art. Developing a student as a “work of art” in itself requires thought of someone that approaches teaching itself as an art form and then superimposes his educational art upon his artistic craft of musical performance.

We notice an aged man, mature, detailed down to the lines and wrinkles of his old worn face and beard. The artist created this drawing not by drawing each feature perfectly and independently of the other. He drew it by first outlining his basic facial structure and slowly adding general details of each feature and finally by adding the final details which distinguishes this man as a unique individual.

I think by approaching music teaching from this perspective will provide us with an approach that will keep us from an ill advised fastidiousness to detail, that I fell into in my early teaching career, to a panoramic view with an eye to the end that still begins with the very first lesson.